The Science in 30 Seconds

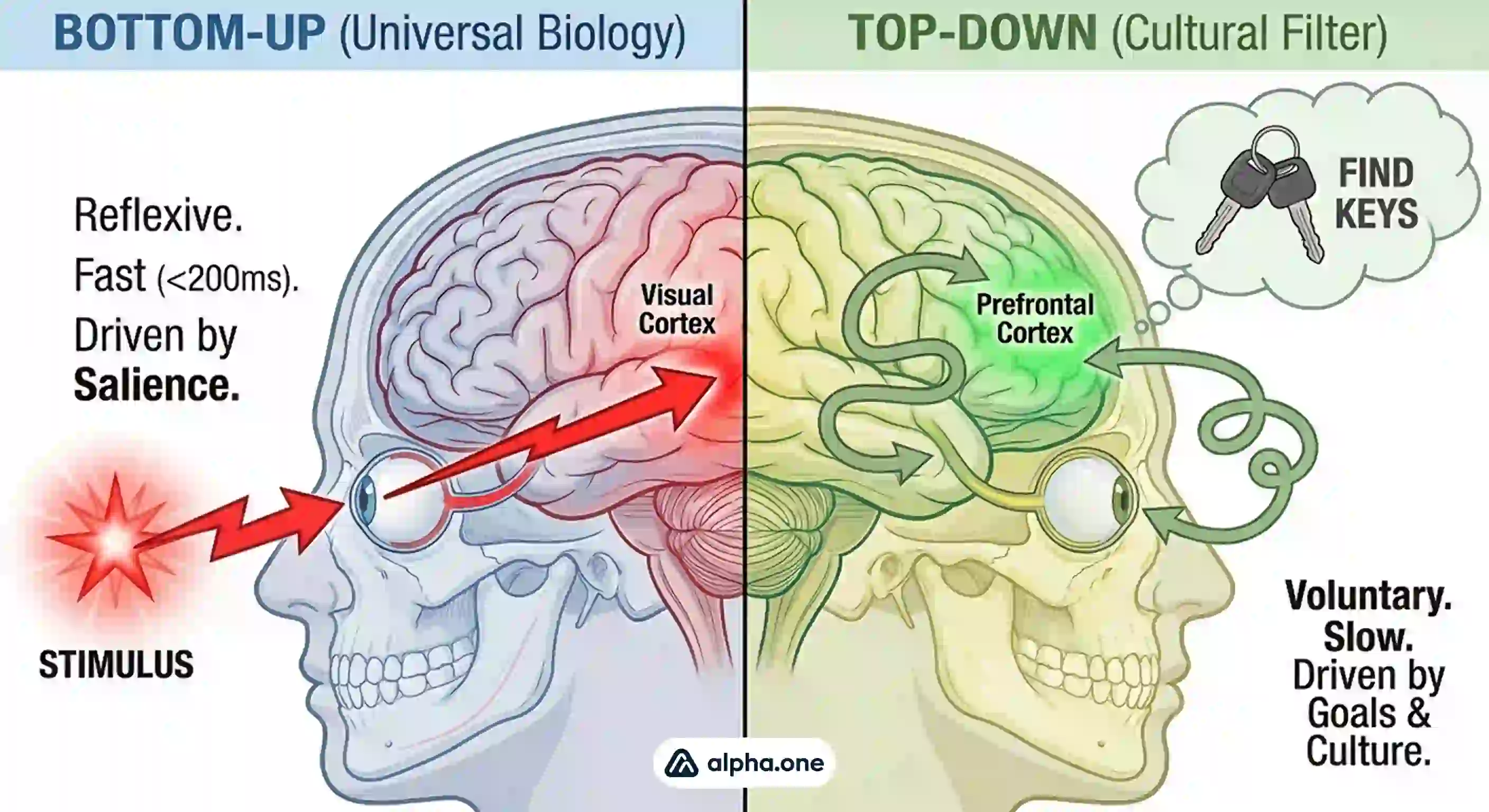

- The Core Conflict: While culture shapes how we interpret meaning (Top-Down attention), biology dictates where we look first (Bottom-Up attention).

- The Universal Truth: Neuroscience confirms that Visual Salience (contrast/brightness), Face Perception, and Primacy/Recency effects are hardwired and work identically across all cultures.

- The Cultural Nuance: Western viewers focus faster on central objects (Analytic), while Eastern viewers spend more time scanning the background context (Holistic).

- The Verdict: Global ad campaigns do not need to be reinvented from scratch. If you optimize for biological salience (using tools like junbi), you capture attention everywhere.

Marketing has a "WEIRD" problem.

For decades, the vast majority of psychological research has been conducted on subjects from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic societies (Henrich et al., 2010). This bias leads to a terrifying question for global brands: Do our advertising benchmarks actually work in Asia, Africa, or Latin America?

If an ad is optimized for a German audience using AI trained on Western data, will it fail in Japan?

The answer lies in the architecture of the human brain. While culture deeply shapes how we interpret meaning, neuroscience reveals that the mechanism of how we pay attention—the raw, biological reflex—is surprisingly universal.

Here is the science of the global brain, and why a good ad in New York is (mostly) a good ad in Nairobi.

The Two Layers of Vision: Biology vs. Culture

To understand cross-cultural attention, we must distinguish between two types of neural processing: Bottom-Up and Top-Down.

1. Bottom-Up Attention (The Biological Universal)

This is the "lizard brain" reaction. It is reflexive, unconscious, and fast (under 200 milliseconds). When you hear a loud bang or see a bright flash of red, you look at it before you even know what it is.

According to Itti & Koch (2001), this system is driven by Salience—primitive visual features like:

- Contrast (Light on dark)

- Orientation (A tilted object among straight ones)

- Intensity (Bright colors)

This layer is universal. A high-contrast logo popping against a black background triggers the distinct neural firing in the primary visual cortex (V1) of a viewer in Seoul just as it does for a viewer in San Francisco. Evolution did not design different reflex systems for different continents; we all needed to spot the predator in the grass.

2. Top-Down Attention (The Cultural Filter)

This is where culture enters the chat. Top-down attention is goal-driven and voluntary. It is the "Search" mode. If you are looking for your keys, your brain biases your attention toward "shiny" and "metallic" objects.

This layer is influenced by culture. Research shows that our upbringing teaches us "where to look" when we are trying to understand a scene.

The Great Divide: Analytic vs. Holistic Vision

The most robust finding in cross-cultural vision science is the difference between Analytic (Western) and Holistic (Eastern) processing.

Masuda & Nisbett (2001) established this distinction by tracking how participants viewed underwater scenes. They found that Western viewers tended to lock onto Focal Objects (the active subject), while East Asian viewers allocated significantly more attention to the Context (the background elements and relationships between objects).

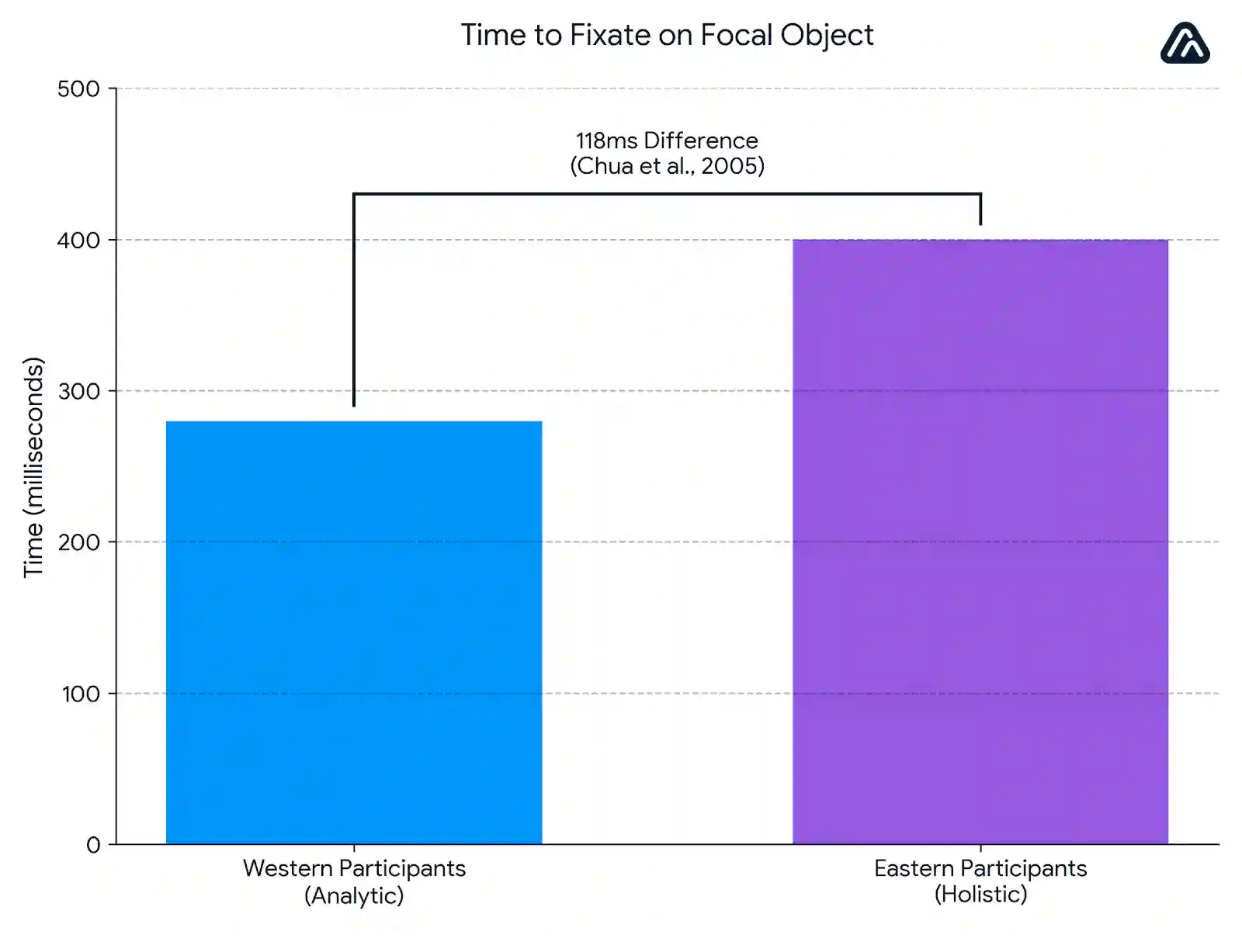

The Evidence: The 118-Millisecond Gap

How deep do these differences go? Researchers Chua, Boland, and Nisbett (2005) used eye-tracking to solve this debate. They showed American and Chinese participants images of a focal object (like a tiger) against a complex background.

The results revealed a distinct "cultural signature" in eye movement:

- The Western Pattern: American participants locked onto the focal object 118 milliseconds faster than their Chinese counterparts.

- The Eastern Pattern: Chinese participants made significantly more saccades (eye movements) to the background context.

But here is the critical find for advertisers: Both groups did look at the focal object. The biological "magnet" of the main subject worked on everyone; the difference was merely in how much extra time was spent checking the background context. This confirms that while culture dictates the scan path, biology dictates the focal point.

The Universal Constants of Ad Performance

Despite these top-down cultural nuances, three biological pillars of attention remain constant globally.

1. The Face Bias

The Fusiform Face Area (FFA) is a specialized region of the brain dedicated solely to processing faces. This is hardwired; even infants mere hours old show a preference for face-like patterns over other stimuli (Johnson et al., 1991).

Regardless of whether your audience is in Brazil or Belgium, a face looking directly at the camera effectively "hijacks" the visual system. It creates an emotional anchor that transcends language.

2. The Primacy and Recency Effects

How we remember ads is also biologically constrained by the architecture of memory. The Primacy Effect (remembering the beginning) and Recency Effect (remembering the end) are universal phenomena of the hippocampus and short-term memory buffers (Murdock, 1962).

- Global Rule: Placing your brand logo at the very start (Primacy) and very end (Recency) of a video asset is effective in every market. The human brain’s "save button" works the same way everywhere.

3. Visual Clutter (Cognitive Load)

While East Asian cultures may have a higher tolerance for visual complexity due to holistic processing styles, the limit of human working memory is a biological hard cap.

"Cognitive Load" refers to the amount of information the working memory can hold at once. When an ad is overloaded with text, rapid cuts, and flashing graphics, it causes Visual Clutter. This leads to "shutdown"—the viewer disengages. No culture is immune to a bad, cluttered ad.

What This Means for Your Global Strategy

If you are running a global campaign, you do not need to redesign your creative from scratch for every market. You need to respect the hierarchy of vision.

1. Optimize for Biology First: Use testing tools to ensure your ad passes the "Salience" test. Is the brand visible? Is the focal point clear? These are bottom-up metrics that apply to all humans.

2. Adjust for Culture Second:

For Western Markets (US, UK, DE): You can afford to be minimalist. Focus heavily on the product in isolation.

For Eastern Markets (CN, JP, KR): You may need to provide more context. Show the product in use within a scene. A floating shoe on a white background might feel "incomplete" to a holistic viewer.

Does AI Scoring Work Globally?

Yes. Because alpha.one’s tools are built on the foundational principles of visual salience and processing speed (bottom-up attention), they predict the immediate, reflexive human response.

While a viewer in Tokyo might process the meaning of your ad differently than a viewer in Toronto, both will instinctively look at the bright red soda can entering the frame at 0:03.

Attention is the door. Culture is the room. You need biology to get them through the door.

Ready to open the door?

Ensure your creative passes the universal biological baseline before you launch in any market.

Claim Your Free Ad Test with junbi

_______

References

Chua, H. F., Boland, J. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (2005). Cultural variation in eye movements during scene perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(35), 12629-12633.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83.

Itti, L., & Koch, C. (2001). Computational modelling of visual attention. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2(3), 194-203.

Johnson, M. H., Dziurawiec, S., Ellis, H., & Morton, J. (1991). Newborns' preferential tracking of face-like stimuli and its subsequent decline. Cognition, 40(1-2), 1-19.

Masuda, T., & Nisbett, R. E. (2001). Attending holistically versus analytically: Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 922–934.

Murdock, B. B. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(5), 482–488.

About the Imagery The visual elements in this post, including the hero image and technical figures, were co-created with Gemini AI. They have been stylized to match a custom color palette (#061E33, #0096FA, etc.) to ensure a consistent aesthetic across this project.